by Elizabeth Hughes, Senior Director of Insight RegionTM

Northern Virginia is one of the country’s most expensive places to live, but also one of its most affordable.

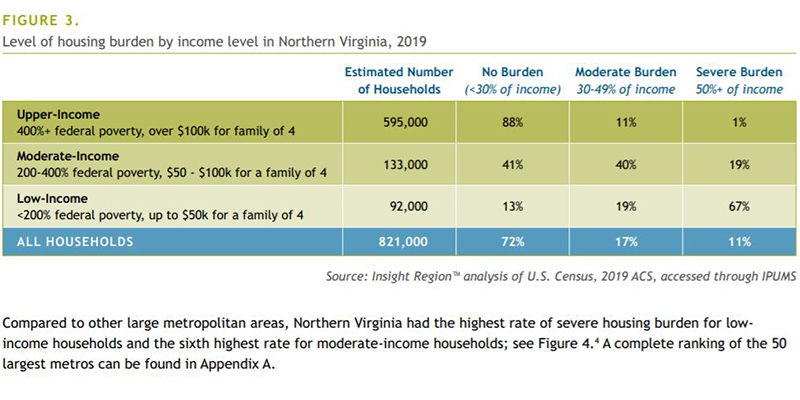

Now, I know how that sounds. But look at the data—in 2019, Loudoun County had the fourth highest median housing cost among all counties and independent cities in the country, followed by Fairfax (#8), Arlington (#10), Prince William (#24), and Alexandria (#26). The same year, 72% of households had housing costs that were considered “affordable” by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and just 11% were considered severely burdened by housing costs, a rate well below the national average (14%) and other tech hubs.

How could the region both be one of the most expensive places to live while also being one of the most affordable? The answer came down to income; with equally high incomes, most Northern Virginians are able to afford the region’s high housing costs. Like any good researcher, I realized that if we wanted to really examine housing affordability, we had to look at how the condition varied by income level.

The results of this inquiry—captured in Insight Region’s most recent brief, Unequal Burden—were truly astounding. Two-thirds of Northern Virginia’s low-income households were severely burdened by housing costs, the highest rate observed in the top 50 most populous metro areas. About one in five moderate-income households also faced a severe housing burden, the sixth highest rate nationally.*

What does this mean? Statistically, very few individuals and families can spend half of their income on housing and remain self-sufficient; for example, a family of four earning $100,000 (the upper bound of “moderate” income households) that spends half of their money on housing would come up about $1,700 short each month. This condition of shelter poverty—lack of self-sufficiency specifically due to high housing costs—limits the quality of life in the short-term and constrains economic opportunity in the long-term. In the wake of economic hardship (such as lost wages due to COVID-19 or unexpected medical bills), individuals and families who were already living paycheck to paycheck may be completely devastated. For those with the means to move, it may be the final push out of Northern Virginia.

I recognize that these findings do not come as a surprise to the individuals and families who cannot afford to live here without ‘cutting corners’ or to the policy experts and advocates who have studied and fought for affordable housing and for living-wage jobs for decades (e.g., see the recent reports on the topic by the Urban Institute and the Northern Virginia Affordable Housing Alliance). But they surprised me—I knew that housing costs were high but not the extent to which they burdened so many of my neighbors or the impact they will have on our ability to grow an inclusive, equitable region. My hope is that this work adds a new data point to the story, sparking conversation, and encouraging action.

In the coming months, I will add to this discussion by examining the state of economic mobility in our region, looking at the factors that help low-income children realize a higher standard of living as adults. It turns out that where we live—and where we can afford to live—matters quite a bit.

* These findings come with a few caveats. First, my definition of “low-income” is based on a household’s percent of federal poverty, which takes into account household size and composition but is not adjusted for area median income. Second, I compare rates of housing burden in Northern Virginia to other metro areas, which is acceptable because Northern Virginia has its own separate urban core and center of economic activity (Fairfax County) but is not a perfect comparison since our region is technically part of the broader DC metro area. If that broader metro area were ranked among the 50 most populous metros, it would be #3 for the highest rate of severe housing burden among low-income households and #8 for the highest rate among moderate-income households.

Questions?

Questions? Questions?

Questions?